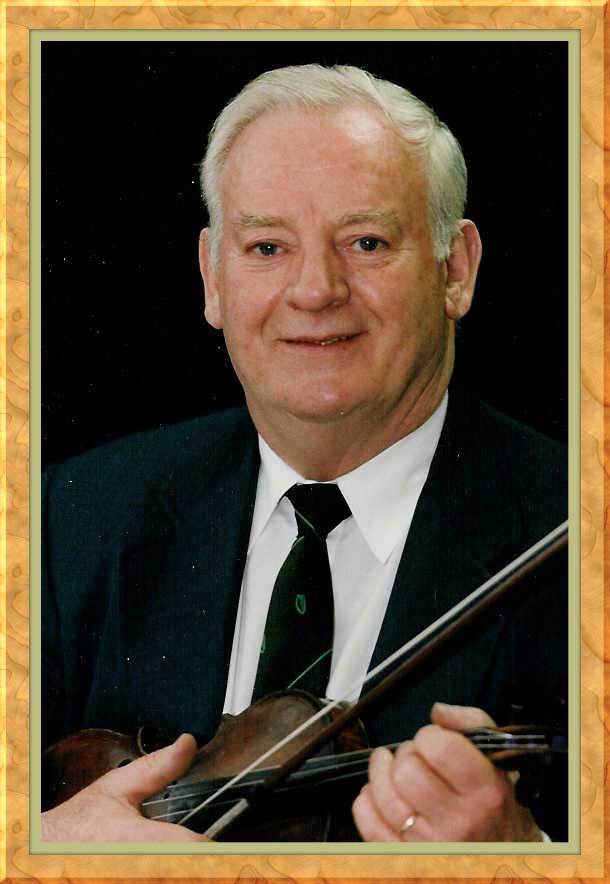

Larry Reynolds, Sr., former Chairman of the Reynolds-Hanafin-Cooley branch of Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, was inducted into The Hall of Fame by The Northeast Region of the North American Province on November 9, 2002.

Widely Praised for His Fiddle Playing

Articles about Larry Reynolds by the Irish Echo, Boston Irish Tourism Association, and The Boston Globe

From The Irish Echo issue of December 17-23, 2003.

Harvard Praises the Bard of Ballinasloe

By Michael P. Quinlin

The scene might have come right from an old Irish saga. On a cold winter’s night recently Gaelic scholars and Irish leaders gathered at the Loeb House at Harvard University, in a lavish dining hall seeped in tradition.

With fireplace blazing and chandeliers low, forty invited guests sat down to a formal pheasant dinner and an evening of toasts, stories, laughter and a few tears in honor of local fiddler and traditional music impresario Larry Reynolds and his wife Phyllis.

Reynolds was praised for his generous and unflinching devotion to traditional Irish music in Boston, a devotion that covers half a century. He follows in the footsteps of other prominent men and women to receive the honor, including poet Seamus Heaney, politician Billy Bulger, former Consul General Orla O’Hanrahan and University of Ulster president Gerry McKenna.

“Larry got two standing ovations during the evening, putting him on a par with Seamus Heaney, whom we honored back in 1997,” said Philip C. Haughey, chairman of Harvard’s Friends of Celtic Studies, which hosted the event. The group raises funds to help graduate students carry out research on ancient Gaelic texts.

Joining Haughey and the Reynolds at the soiree was Dr. Patrick K. Ford, head of Harvard’s Celtic department, Tomas O Cathasaigh, professor of Irish Studies, and Friends committee members Gene Haley, Mary McMillan and Elizabeth Gray.

Representing Boston’s Irish community were Isolde Moylan, Consul General of Ireland, David and Pat Burke and Robert Collins of the Irish Foundation, Mike and Liz O’Connor and Brian O’Donovan of the Irish Cultural Centre, and Seamus Connolly, head of the Gaelic Roots program at Boston College. Comhaltas officials Barbara Davis, Jimmy Roche and Tom Concannon also attended.

Connolly, considered one of Ireland’s finest fiddlers, praised the work that Reynolds and his family has put into Irish music over the last fifty years.

“I don’t know of anyone outside of Ireland who has done more to promote Irish traditional music than Larry Reynolds,” Connolly said. “He has helped scores of young musicians fresh off the boat, giving them money out of his own pocket and setting them up with gigs. When I first came here in 1975, he gave me my start.”

Connolly also credited Reynolds for helping to make Comhaltas Ceoltoiri Eireann such a vibrant group with chapters all over the year, of which Boston’s is among the largest.

“The Irish government should give Larry an award for the way he’s represented Ireland in America. He is one of Ireland’s best living ambassadors,” Connolly said.

That Reynolds is held in such high regard comes as no surprise to anyone who has lived in the Boston area. He moved here from Ballinasloe in 1953, bringing with him the great musical traditions of East Galway that other musicians like Patsy Touhey, the great piper from Loughrea, brought to Boston before him.

Reynolds arrived at the height of the Dudley Street era in Roxbury, when numerous Irish dance halls created a vibrant dance scene that lasted into the early 1960s. He played with Paddy, Johnny and Mick Cronin from Kerry, Brendan Tonra from Mayo, and a host of American born players like Joe and George Derrane and the late banjo player Jimmy Kelly. He later formed his own groups, the Tara Ceili Band and the Connacht Ceili Band, before devoting himself solely to Comhaltas starting in 1975.

Reynolds also did several gigs for Harvard’s Folk Dance Society during the early 1950s, traveling across the Charles River with musicians Tom Senier and Dessie O’Reagan and dancer Mike Cummings. Reynolds never imagined he would be honored fifty years later.

“I was very proud to be honored by Harvard as a proponent of Irish music,” Reynolds says in retrospect. “For me, it’s a sign that Irish traditional music is now on a plateau where it belongs.”

***********

Harvard’s Irish Connections

Harvard’s connections to the Irish community date back to 1896, when Chaucer scholar Fred Norris Robinson taught the first Gaelic course in America at the college.

Robinson grew up in Lawrence, a mill city north of Boston that was so heavily Irish it even had its own Irish language newspaper, notes Dave Burke of the Irish Foundation. An active member of the Irish community, Robinson helped to welcome Dr. Douglas Hyde to Boston in December 1905, and took part in numerous activities hosted by the Gaelic League. He taught Irish and Welsh at Harvard for forty years before the school formally created a Celtic Studies department, thanks to a donation of $51,000 from philanthropist Henry Lee Shattuck on behalf of the Charitable Irish Society.

Thanks to Dr. Ford and Phil Haughey, the Celtic Studies Department today remains active in the Irish community at-large. It has partnered with Boston College’s Irish Studies Programs, and supports local cultural groups like Sugan Theatre. Each October it hosts an annual colloquium that features the latest research of Celtic scholars and graduate students from across the world.

The Department has recently initiated an effort to endow a lecture series in honor of Professor John V. Kelleher, another native of Lawrence who was department chairman from 1962 to 1984. Kelleher is credited, along with Eoin McKiernan and others, of helping to establish Irish Studies as a legitimate discipline in American colleges. Now retired, Kelleher continues to inspire students of Celtic Studies, Ford noted.

Reynolds, meanwhile, continues his role as Ireland’s ambassador of Irish music, a duty he has also passed along to his sons Larry, Michael and Sean. As comfortable on a college campus as he is in a dance hall or pub session, Reynolds and his good friend Seamus Connolly are now regular attendees at the gatherings hosted by the Friends of Harvard Celtic Studies. When they take out their fiddles and start up a few tunes, it brings smiles and nods of approval from the Celtic scholars in their midst.

(Printed here with permission) (c) 2004 Irish Echo Newspaper Corp.

Larry Reynolds

Fiddle Player

From Ballinasloe to Boston, people know the name Larry Reynolds, and why won’t they? The gregarious, genial fiddle player has been a central figure in Irish music circles for over half a century, and has been perhaps the major influence in popularizing Irish traditional music throughout New England.

Reynolds has lived in the Boston area since 1953, emigrating from Ballinasloe, Galway as a young man, fiddle case in hand. He quickly got into the thriving dance hall scene along Boston’s Dudley Street in Roxbury, playing with musical greats Paddy and Johnny Cronin, Joe Derrane, Brendan Tonra and others.

Over the years, Reynolds has led traditional Irish music sessions regularly at places like the Green Briar Pub in Brighton and the Canadian American Hall in Watertown. The late Congressman Tip O’Neill used to call him whenever the Cambridge pol needed to unwind and sing a few old-style Donegal songs that only Reynolds and his good friend fiddler Seamus Connolly knew. Political chieftain Billy Bulger relied on Reynolds for many a political time in South Boston, and he has played for Irish presidents Mary Robinson and Mary McAleese.

In 1975 Reynolds helped form the Boston Chapter of Comhaltas Ceoltoiri Eireann (Irish Musicians Association), turning it into one of the largest branches in the group’s worldwide network. He has recorded on several albums, including the classic “We’re Irish Still”, and was featured along with his sons in the opening wedding scene of the movie “Blown Away.“

For such an affable and public figure, Reynolds has spent his career shunning the accolades that others try to bestow on him. A few years ago his Boston friends put together a tribute dinner for him, and over 1,000 people showed up, many of them traveling from around the world. In 2003 Harvard University’s Celtic Department honored him for ‘the enormous contributions to Irish culture in Boston.’ He was inducted into the Comhaltas Hall of Fame and was honored by the Irish Cultural Centre of New England. In 2006 he was named one of the Top 100 Irish-Americans by Irish America Magazine in New York.

While all of this music-making was taking place, Reynolds earned his living as a master carpenter, working on many of Boston’s finest buildings. He and his lovely wife Phyllis live in Waltham, where they raised five sons and a daughter, all of whom took up Irish music. Today the Reynolds have nineteen grandchildren and one great grandchild, enough to form a couple of ceili bands.

by Michael P. Quinlin

Boston Globe Article: “Larry Reynolds, fiddler of local renown, is mourned”

Bill Brett For The Boston Globe

The crowd of mourners at the funeral Mass of Larry Reynolds, 80, spilled out of St. Jude Church and on to Main Street in Waltham on Thursday.

Frank Joyce had to keep his funeral home in Waltham open a lot later than planned Wednesday night. Larry Reynolds’s wake was supposed to last for six hours. But it took more than nine hours to get everybody through the line.

“At least a couple of thousand people,” Joyce said. “They just kept coming.”

It seemed like half of them returned to Waltham on Thursday morning, to St. Jude Church, where Larry Reynolds was dispatched from this world with the two things that embodied him: kind words and beautiful music.A Waltham cop, perplexed by the size of the crowd that spilled out of the church onto Main Street, tugged at a photographer and asked, “Who was this guy?”

Larry Reynolds grew up in a village called Ahascragh, in County Galway, in the west of Ireland. When he was 10, his brother Harry bought him a fiddle and his sister Betty, who was working as a maid for a wealthy family, paid for lessons. He was schooled in the traditional style peculiar to East Galway, and he played for love, not money.

But money was scarce and so, like many Galwaymen of his generation, Reynolds immigrated to Boston. He was 20 years old when he got here in 1953. He fed his stomach by working as a carpenter. He fed his soul by playing his fiddle. He used his bow like a saw, to build something that would last.

If the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem led the renaissance of traditional Irish music worldwide, Larry Reynolds led it here in and around Boston. When he first got here, he played at Hibernian Hall in Dudley Square in Roxbury. He took the music to the suburbs, playing at the Village Coach House in Brookline, the Skellig in Waltham.

His hands were a contradiction. The skin that covered them was coarse, the skin of a working man who swung a hammer. But his fingers were the digits of an artist, as dexterous as a surgeon’s. For all his talent, he was a humble man. He blushed at praise. He carried his union card, Carpenters Local 67, and his fiddle case wherever he went.

He was an easy man to find on Monday nights. For a quarter century, you could find him every Monday, sitting in the Green Briar, a pub in Brighton. He didn’t go there to drink. He went there to play music, to teach music, to evangelize, really. He was a missionary, spreading the good news. Traditional music was a restorative force to Reynolds, a relaxing, mystic tonic for increasingly frenetic times.

His weekly trad sessions were low-key revival meetings. People — young and old, Irish and mostly not Irish — came to sit at Larry Reynolds’ elbow, the fiddler’s elbow. Reynolds played with some great musicians, but he liked nothing more than coaxing novices to put aside their nervousness and give it a go: a teenager shyly holding a tin whistle, an old woman trying to master the bodhran drum. A whispered word from Larry Reynolds was usually all it took for someone to lose their stage fright.

His wife, Phyllis, is an accomplished pianist, and she threw open their Waltham home to a never-ending stream of musicians and dancers and singers. Larry and Phyllis Reynolds were married for 58 years, had seven kids, and gave birth to countless musicians.

It is not an exaggeration to say that thousands of people, many of them without anything remotely Irish about them, became purveyors or lovers of traditional music because of Larry Reynolds.

And that is why, in this day and age of celebrity, thousands of people came to Waltham to say goodbye to someone who was neither rich nor famous.

Even at 80, Reynolds was in no rush to leave this world. But he would have enjoyed his funeral. He always found the liturgy of the Mass comforting. And there were even more musicians than priests in the church, and they sent him off with a slow air, “For Ireland I’d Not Tell Her Name,” which he loved.

His impact will last as long as the music. And that’s forever.

Kevin Cullen is a Globe columnist. He can be reached at cullen@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @GlobeCullen.

http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2012/10/11/honoring-tradition-larry-reynolds-fiddler-local-renown-mourned/96zwjB52KhFcLEFS0JWUQK/story.html

Influenced Development of Comhaltas Branch

- [to be updated]

Accomplishments

Teaching Credits

- [to be updated]

- Awards

- [to be updated]

Audio Recordings

- [to be updated]

Larry Tormey wrote this article and updated it in 2012:

CCE Northeast Regional Hall of Fame Inductee

Larry Reynolds, Sr. – Fiddle

Inducted to its The Hall of Fame by

The Northeast Region of the North American Province – November 9, 2002

Larry Reynolds, Sr.- (fiddle) was born in a little town called Ahascragh in Co. Galway in 1932—the 12th of 13 children, 6 girls and 7 boys. He began to learn the fiddle at age 10 when his brother Harry bought one for him. His sister Betty, working as a domestic for a family in Ballinasloe, paid 30 shillings a quarter for Larry, for lessons from Mabel West. Larry says that he always enjoyed the traditional music, listening to it over the radio whenever the opportunity presented itself.

Larry’s boyhood home was a well-known gathering place for music and house dancing, where there was “never a shortage of either.” He played with a couple of different bands in Ireland before emigrating to Boston in 1953, where he met his future wife Phyllis, a piano player. They were married and blessed with 7 children—6 boys and 1 girl. Over the years, Phyllis imparted her knowledge of music to their children, meanwhile graciously hosting in their Waltham home innumerable musicians, singers, dancers, and friends from the U.S. and Ireland.

Since coming to the States in the 50s, Larry has played with several groups: The Tara Ceili Band, The Connaught Ceili Band, The Boston Ceili Band, Tommy Sheridan Band, Tara Hill, and The Boston Comhaltas Ceili Band. Larry recorded with The Connaught Ceili Band, and with Comhaltas band members and guests on the album We’re Irish Still (1980). Having hosted the Comhaltas Concert Tour Group in 1973, ’74, and ’75, Larry and others founded the Boston Hanafin-Cooley Branch of CCE in Boston in 1976, and have hosted the tour group every year since (except in 2001, when the tour was cancelled). He is also Treasurer of the North American Provincial Council of CCE. Having always enjoyed his association with Comhaltas, he can’t imagine not being involved, he says, in promoting Ireland and her music, with the help of his wife Phyllis, their family and their many friends.

In 1984, Seamus Connolly and Larry began broadcasting a one-hour radio program on station WNTN Boston, Saturday mornings. When Seamus became busier organizing the Gaelic Roots Festival, Larry’s son Sean stepped in to help. Larry and Sean continue to host the 1-1/2_ hour broadcast from noon to 1:30 p.m. every Saturday (Eastern Standard Time)—heard live around the world on www.wntn.com.

**************************************************************************

The Boston Comhaltas Ceili Band, formed in 1976, grew naturally out of sessions and musical friendships. Current band members Larry Reynolds, Sr. and Tom Sheridan played with the old Boston Ceili Band of the 50s. The current band has played out for more than 15 years, performing from Alaska to the Grecian Islands to the Caribbean, from Cleveland in the mid-west to Cape Cod in the East, at ceilis in resort hotels in the Catskills and at fabulous hotels in downtown New York City. Ready to play at both local benefits and major Irish music festivals, the band has built their reputation also in part upon their great musical depth. Seamus Connolly plays with the band occasionally. Larry Reynolds, Sr. and his sons Mike and Sean, his nephew Pat, and father and son Fergus and John Keane are band regulars. Other fine musicians play now and then: Tara Lynch, Tom Sheridan, Jimmy Hogan, and Martin Cloonan among them.

**************************************************************************

Return to Hall of Fame

Page revised 12/5/2012